Many people will face kidney stones at some point in their lives. According to estimates from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, around 12 percent of the population experiences these small but painful formations.

Men are more likely to develop them than women, yet the gap appears to be narrowing.

Some stones don’t cause symptoms right away. Others lead to excruciating pain, often described as one of the most intense sensations a person can endure.

While kidney stones can vary in size, even the tiniest crystal can trigger discomfort and send patients rushing to the emergency room.

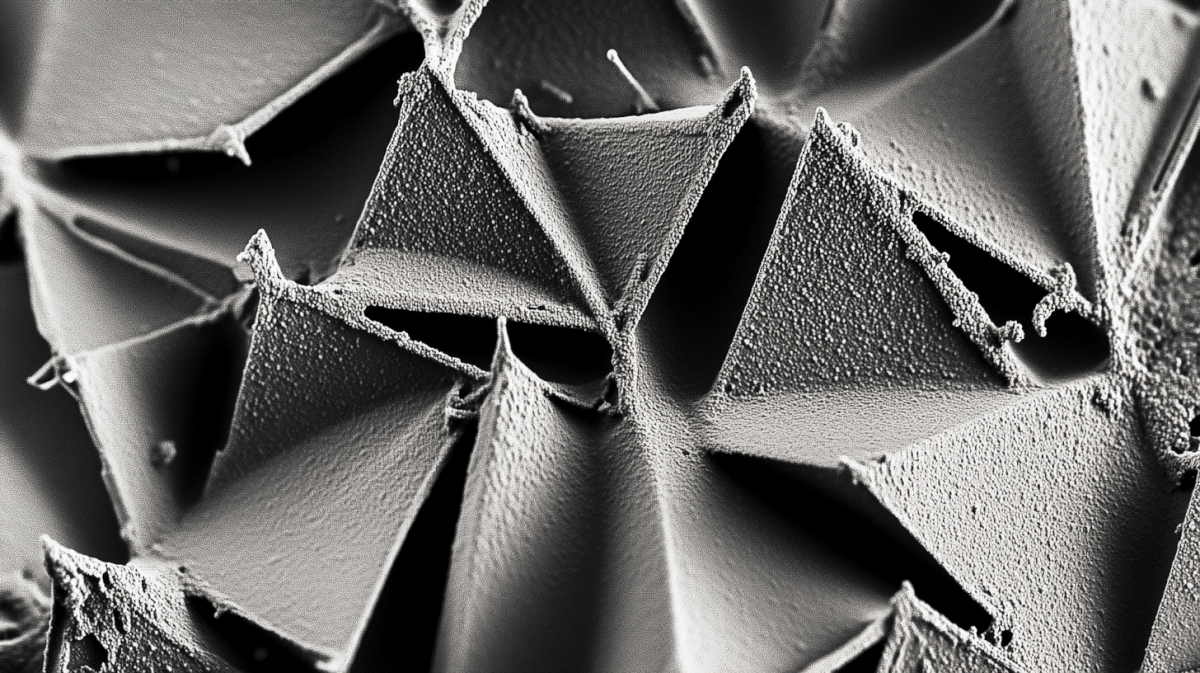

Beneath powerful microscopes, kidney stones reveal hidden structures. Jagged edges and crystalline surfaces form intricate patterns that help scientists identify how these stones develop and how they might be prevented.

By studying them under scanning electron microscopy, researchers discover clues about the body’s chemistry and the factors that allow small clusters of minerals to grow into troublesome stones.

Below, we explore five key findings from microscopic images of kidney stones. We’ll delve into the nature of these sharp formations, explain how layering patterns hold a record of stone growth, and consider why certain minerals form more frequently than others.

1) Crystal Composition and Formation

Kidney stones form when substances in the urine, such as calcium, oxalate, phosphate, or uric acid, cluster into crystals. Over time, these crystals can grow as more minerals bind to them.

Calcium oxalate stones are the most frequent. Under a microscope, they appear jagged and glass-like. Sometimes they look like tiny shards of broken quartz. Color varies according to the minerals involved. Darker stones often contain higher amounts of calcium oxalate, while yellowish or tan shades may indicate uric acid.

When scientists examine kidney stones up close, they can see how rapidly they formed. Stones that build quickly often show disorganized patterns of crystal growth. Stones that develop more gradually may feature neat layers of crystals stacked over time.

This microscopic perspective offers vital insights for doctors. It reveals how diet, fluid intake, and even genetic predispositions can shape the internal environment of the urinary tract.

2) Layering Patterns Reveal History

In much the same way tree rings capture decades of growth, kidney stones display layers that document changes within the body. These rings emerge during periods when mineral buildup fluctuates.

Under fluorescent microscopes, scientists can illuminate these layers in striking detail. Different phases of crystal growth become visible, sometimes revealing breaks or dissolved segments where the stone partially disintegrated before regrowing.

Light and dark bands indicate changing urine chemistry, which can be linked to hydration levels, diet, or even short-term medical treatments.

Layer thickness can also show how quickly the stone formed. A stone that develops rapidly may exhibit fewer, thicker layers, while a stone that grows slowly over months might have more delicate layers. This record of stone formation helps healthcare providers pinpoint when and why certain minerals began clustering.

It can also highlight periods of inflammation or infection. Knowing the stone’s growth pattern is essential for tailoring treatment strategies, from dietary changes to medications that balance urinary pH.

3) Common Minerals and Their Implications

Calcium oxalate is the top culprit in kidney stone formation, but it’s not the only one. Other types carry distinct clues about a person’s health.

• Calcium Oxalate

Sharp, jagged formations. Often tied to diets high in oxalate (found in foods like spinach and nuts) or to conditions like hyperparathyroidism.

• Calcium Phosphate

Smooth, rounded stones. They can arise from a more alkaline urine environment or an imbalance in acid-base regulation within the body.

• Uric Acid

Typically yellow or brown. Linked to high protein diets, gout, or inherited metabolic conditions. Microscopic views show smaller, crystal-like clumps that can be harder to detect on X-rays.

• Struvite

Usually form in the presence of urinary tract infections caused by specific bacteria. Rectangular or coffin-lid shaped crystals are common indicators when viewed under magnification.

Analyzing these stones helps doctors determine the best treatment. Uric acid stones, for example, may respond to medications that alkalinize the urine, while struvite stones require careful management of infection.

Microscopic evidence can also reveal mixed compositions. Some stones contain layers of different minerals, showing how multiple processes may have contributed to their formation.

4) Calcium Oxalate’s Jagged Profiles

Calcium oxalate stones can be split into two main categories, monohydrate and dihydrate, each forming distinct patterns under the microscope.

Monohydrate stones often have smoother surfaces, though they’re still quite hard. Dihydrate stones typically feature needle-like or spiky edges. This difference matters because the dihydrate form can sometimes develop more quickly, leading to sudden symptoms and potential blockages in the urinary tract.

Researchers studying these stones notice how easily they can embed themselves into the kidney’s lining. Tiny projections may latch onto spots where plaques of calcium phosphate (known as Randall’s plaque) accumulate. When these attachments take hold, stones can gain size rapidly.

Viewing these formations under scanning electron microscopy (SEM) clarifies their surfaces in great detail. Doctors use these images to determine stone composition and to counsel patients on ways to reduce calcium or oxalate intake. Appropriate hydration is also crucial. Drinking enough fluids can dilute the urine, making it harder for crystals to cluster.

5) The Fluorescent View of Stone Growth

Fluorescent microscopy adds another dimension to stone analysis. Researchers slice or grind stones into thin samples, then examine them under special lights that cause certain minerals to glow. This approach reveals internal layers with precision, highlighting transitions between different mineral types.

Scientists often look for Randall’s plaque, a starting point for many kidney stones. Fluorescence makes it easier to see spots where calcium deposits begin, especially in early stone formation. Sometimes, these plaques exist silently, waiting for a trigger—like dehydration or changes in pH—that allows a stone to take shape.

This technique also shows how stones can partially dissolve, leaving gaps or cracks in the structure. When conditions revert to favor stone formation, minerals deposit again, creating new layers. Each gap reflects a shift in a person’s internal chemistry, such as dietary changes or medication use.

By combining fluorescent microscopy with other imaging methods, researchers build a more complete picture of how kidney stones develop. They track when crystals started and how external factors influenced growth or dissolution.

Leave a comment